The Losing US Strategy in Southeast Asia and How to Fix It

U.S. President Joe Biden with ASEAN leaders during a special summit at the White House. Photo: REUTERS/Leah Millis

“The ASEAN centrality is the very heart of my administration’s strategy in pursuing the future we all want to see. And I mean that sincerely.”

As Southeast Asia shapes up to be a key geopolitical and economic battleground, Biden’s emphasis on ASEAN centrality seems self-evident. This year, the region is getting more attention as it plays a larger role in global politics with the hosting of three international events: the G-20 summit in Indonesia, the ASEAN summit in Cambodia and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation organization meetings in Thailand.

But amidst the ongoing political tug of war between the US and China, Biden first has to establish what ASEAN centrality means.

With geopolitical upheavals dividing Southeast Asia, there is little evidence that all Indo-Pacific states have ever perceived a single unifying source of regional legitimacy. The concept of neutrality then becomes problematic as ASEAN does not have an agreed-on common policy, with the use of neutrality creating confusion.

This confusion can be continuously seen with regards to foreign affairs, as its members often showcasing different stances. A recent example would be the Russia-Ukraine War.

Thailand supported motions against the war while Vietnam took a more pro-Russian stance by voting against ejecting Russia from the U.N. Human Rights Council. The remaining members seem to interpret neutrality as not taking a side rather than upholding the principles of international law.

While such differing stances seem less consequential to events continents away, they become more dangerous with regards to critical challenges surrounding the region. The ongoing turmoil in Myanmar and the continued territorial dispute in the South China Sea undermines the organization as a whole and, according to some critics, it undermines their relevance in the region.

A GIS report recently categorized Southeast Asia into two brackets regarding the US-China rivalry – more authoritarian leaders lined up with Beijing and the rest with Washington.

Cambodia and Laos, are the biggest proponents of China, and Brunei, Myanmar and Thailand lean in a similar direction. Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore tend to lean towards the US. Vietnam is considered an outlier due to its criticism of China on political and security matters, while being heavily dependent on Beijing for trade and investment.

However, there seems to be a trend here: Southeast Asian states rely on China for growth and development while looking to the U.S. for security and protection against Chinese hegemony.

So what now?

The US must have a shift in perception regarding what ASEAN is and represents. The changing geopolitical setting has altered the idea of it as being a unified regional community. The core concept of centrality requires relative peace and a balance of powers in the region. When the big powers are locked in a zero-sum conflict game, ASEAN seems to become divided and ineffective. Each issue pulls different member states in different directions, with each state having their own independent policies that are sacredly protected by the bloc's non-interference principle.

For these reasons, ASEAN must be substantively viewed as an economic organization.

Despite Asia’s rapid economic growth, ASEAN still represents a region of largely developing countries in need of trade, infrastructure investment? and developmental assistance. No nation in Southeast Asia will be willing to trade such tangible benefits for concepts of international order which seemingly hold little immediate relevance to them. China understands this – it navigates constructive diplomacy with economic advantages to weather clashes of interests with individual ASEAN States.

It is about time America takes a page from China's playbook. Economic contributions and diplomatic influence go hand in hand in Southeast Asia. It is economics, not the selective enforcement of human rights or democracy, that most concerns national governments there.

ASEAN members are neither democratic nor liberal. ASEAN's main concerns are peace and stability. And the greatest threat to this peaceful stability is the huge economic hit of the pandemic, with IMF’s recent Asia update providing a bleak future with many economic risks ahead.

So the picture now becomes clearer: Southeast Asia has different functional orders with different actors offering different structures and rules. The Lowy institute, an Australian political think tank, claims that there is now a normative multilateral diplomatic order, with the United States sustaining the region’s military-security order, and China buttressing the economic order.

However, will Washington’s military alliances outlast Beijing’s economic ties in the region?

While there are no definite answers, it seems to be a very dangerous game to play. Economic initiatives are crucial and while overwhelmingly behind, it is not too late for the US to compete with China to build Southeast Asia's next generation of infrastructure.

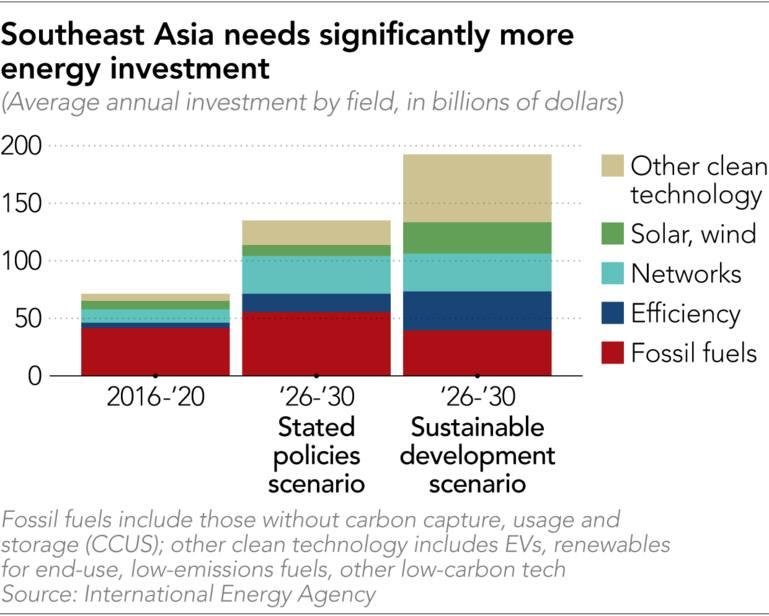

In ASEAN, the next phase of the power battle seems to be clear. The region's energy investment must double the current annual averages to at least $130 billion by 2030 to keep pace with demand, the International Energy Agency says. America can start there.

Projected outlook for Southeast Asia’s energy sector. Source: International Energy Agency

Henry Kissinger, former secretary of state, claims that the American foreign policy trauma of the sixties and seventies was caused by applying valid principles to unsuitable conditions.

This seems especially true with regards to Southeast Asia now. The ASEAN centrality at the heart of Biden’s strategy has at its core, a “rule-based order” narrative. However, geopolitical upheavals in Southeast Asia has meant that this centrality is often inconsistent and muddled.

Therefore, outside of military pacts and showing up for international summits, the Biden administration will now have to translate its newfound diplomatic capital from back-to-back summits into concrete initiatives to credibly compete with Beijing. Be it alone, or with other like-minded partners such as Japan and Australia, economic investment in Southeast Asia is imperative.

The stakes are high. The region has a combined GDP of over $3 trillion and has a young population with an expanding middle class of 680 million people. The complex nature of the region inhibits flexibility, and early choices are especially vital. It’s time for the US to change its strategy and act.

It’s crunch time.